Jason Lawrence Duncan

October 2025

― ✦ ―

For her — the one who taught me that even in suffering, we can still choose kindness.

― ✦ ―

These seven premises form the moral and philosophical scaffolding of the Capybara Doctrine — a compass for action in a complex, imperfect world.

“There are no moral phenomena, only a moral interpretation of phenomena.” — Friedrich Nietzsche1

“An' ye harm none, do what ye will.” — Wiccan2 Rede

“Perfect is the enemy of the good.” — Voltaire3

“That which can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence.” — Christopher Hitchens4

“The only alternative to coexistence is co-destruction.” — Jawarhalal Nehru5

“When you’re dead, you’re dead. But you’re not quite so dead if you contribute something.”

— John Dunsworth6

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice — if we bend it.” — Paraphrasing Martin Luther King Jr.7

* The Wiccan Rede imagines a world where harm is minimized — not

a commandment, but a moral horizon.

Nietzsche dissolves all horizons by denying moral facts; the Rede

restores one, not as law but as longing.

In reality, every action creates ripples. Harm cannot be eliminated,

only reduced. The Rede offers not innocence, but orientation — a compass

for navigating imperfect worlds.*

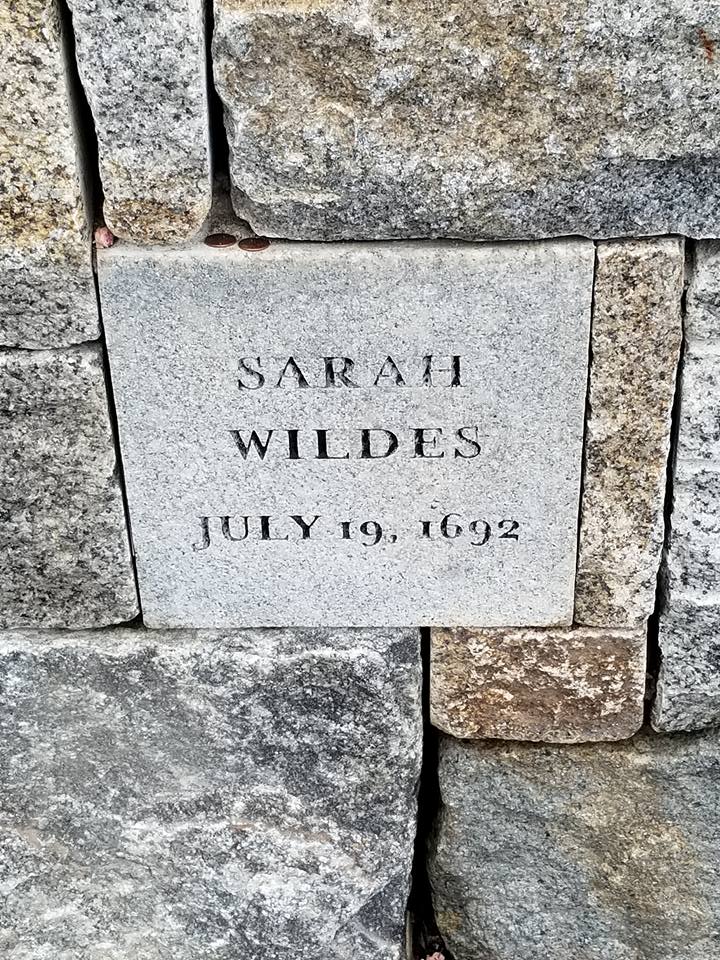

This work explores the ethical imperative of reducing suffering in a universe where moral authority cannot be assumed, inherited, or unquestioned. Morality is framed as an emergent construct, arising from collective human reflection, action, and reflective, iterative learning. It does not derive from static laws or infallible authorities. The work is illustrated through historical and personal case studies — including the Salem Witch Trials, World War II, and Shays’ Rebellion — highlighting the consequences of fear, ideology, and moral courage in contexts of extreme suffering.

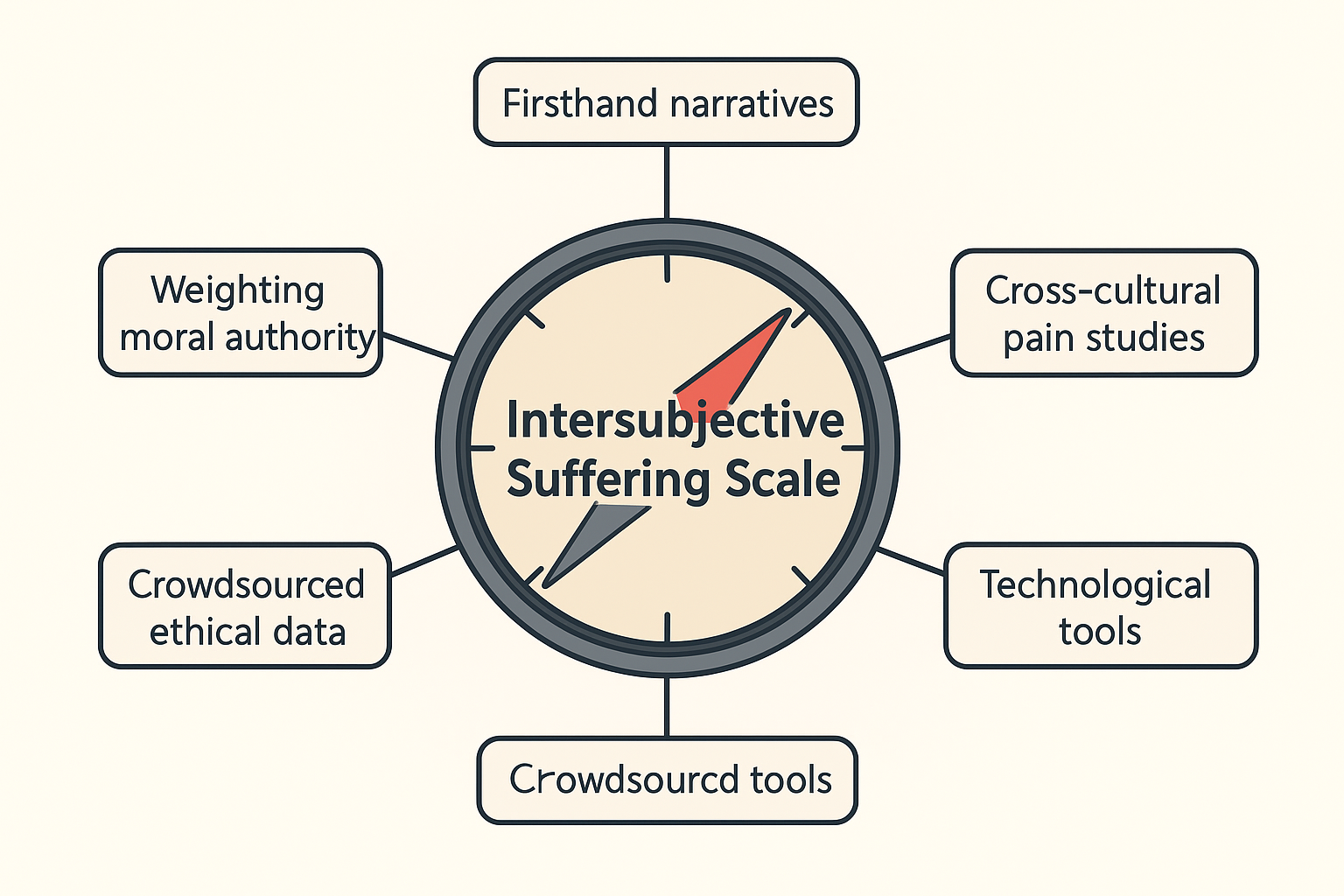

We examine the ethical responsibility inherent in creation — whether technological, biological, or social — and the dangers of unexamined belief systems, including faith without evidence. To operationalize moral action, we propose the Intersubjective Suffering Scale (ISS), a practical framework for estimating, comparing, and prioritizing suffering across contexts, acknowledging both its limitations and its necessity for ethical decision-making.

By embracing skepticism, empathy, and incremental moral action, this ethical framework offers a roadmap for navigating complexity and reducing suffering in an uncertain world — a task whose urgency grows with every new technological, social, and environmental challenge.

November 2025

Since the original publication of the Capybara Doctrine, readers have engaged with its core ideas — Radical Humility, Necessary Restraint, and Shared Space — in philosophical reflection, personal meditation, and ethical thought experiments. Version 2.0 marks a new stage in this ongoing journey: it moves beyond principles alone and embraces practical application, visualization, and lived experimentation.

This edition introduces:

****The How-to Practice Guide** – a step-by-step companion for embedding the Doctrine in daily life. Through exercises, reflective prompts, and iterative methods, readers can cultivate ethical skill in action, not just in thought.*

****Diagrams and Visual Frameworks** – clarifying relationships among principles, companion practices, and the measurement of suffering, helping readers internalize the abstract ideas through concrete, observable models.*

Companion Practices – tools for nuance, ethical integration, and the responsible use of instruments, allowing the Doctrine to remain adaptive, precise, and accountable in a complex world.

Capybara Doctrine 2.0 is not a replacement of the original; it is an expansion. It assumes that ethics is a living process: one that requires observation, reflection, and continuous refinement. In these pages, ideas meet practice, theory meets experimentation, and moral contemplation meets tangible action.

This version is offered as an invitation: to pause, to question, to act gently, and to engage fully with the ethical challenges of modern life. Each exercise, each reflection, each visualization is a chance to practice care, insight, and responsibility — for oneself, for others, and for the wider world we share.

— Jason Lawrence Duncan Author and Originator of The Capybara Doctrine

Version 2.0 — November 2025

This edition represents a significant expansion of the Capybara Doctrine, adding practical tools, visual frameworks, and guidance for daily ethical practice.

How-to Practice Guide

Step-by-step exercises for Radical Humility, Necessary Restraint, and Shared Space.

Companion practices for nuance, tool awareness, and integration.

Reflective prompts to cultivate ethical skill in everyday life.

Visual Diagrams

Conceptual illustrations of the Doctrine’s principles.

Diagrams for ethical loops, interconnected stakeholders, and the Intersubjective Suffering Scale (ISS).

Visual frameworks for clarifying complex ideas and relationships.

Companion Practices

Nuance: guidance for translating principles into context-sensitive action.

Right Use of Tools: ethical reflection on technologies, workflows, and instruments.

Integration Techniques: combining principles and tools into a cohesive daily practice.

Reworked explanations of the principles to include concrete, actionable guidance.

Expanded examples, scenarios, and practice prompts for clarity.

Updated language for accessibility and readability, ensuring ideas are practical for diverse contexts.

Strengthened ethical scaffolding, emphasizing iterative learning, feedback, and responsibility.

This edition is not a replacement, but an expansion of the original Doctrine.

The core principles remain unchanged: Radical Humility, Necessary Restraint, and Shared Space.

New practices and visual aids are intended to translate philosophy into tangible, observable action, supporting reflection, collaboration, and ethical growth.

In a universe of uncertainty, moral clarity cannot be assumed. Humans now wield unprecedented power to create life, intelligence, and artificial worlds, yet the frameworks for ethical governance lag far behind our capacity for impact. Traditional appeals to divine or authoritative moral systems fail under scrutiny. They are often unverifiable, inconsistent, or silent in the face of suffering. If morality cannot be inherited, it must emerge. Emergent morality is not static law but a living, iterative practice shaped by reflection, empathy, and cooperation among conscious beings.

Historical and personal case studies — from the Salem Witch Trials8 to World War II and Shays’ Rebellion9 — illustrate the consequences of unexamined authority, systemic injustice, and moral courage under pressure. This work examines the ethical dimensions of creation, the dangers of unexamined faith, and the challenge of quantifying suffering.

We propose practical tools for moral navigation, including the Intersubjective Suffering Scale, to guide decision-making where stakes are high and suffering is real. At its core, this project asks: how can we take responsibility for the reduction of suffering, build moral knowledge collaboratively and create a society where moral authority is earned, scrutinized, and continuously refined?

This work also challenges a deeper assumption — that the will itself is the source of suffering. Where Schopenhauer10 saw escape in the negation of will, we propose its redemption through direction: the will, consciously restrained, becomes the instrument for reducing suffering rather than generating it.

When considering the moral landscape, we are faced with a stark choice: one of three propositions about suffering must hold:

Suffering does not exist.

All suffering is necessary.

Some suffering is unnecessary.

Ethics begins by confronting which of these statements reflects reality — for it is only by recognizing unnecessary suffering that we can act to reduce it.

We feel pain — and with it, the undeniable reality of suffering.

The The claim that suffering does not exist is contradicted by direct experience. To claim that suffering is imagined or illusory does nothing to negate its felt reality.

To echo Descartes11: I feel pain, therefore suffering exists.

“What does not kill me makes me stronger.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

Even Nietzsche stops short of affirming the second case. While he saw suffering as essential to growth, creativity, and transformation, he also acknowledged that not all suffering serves such ends. Some suffering is senseless, destructive, and corrosive: atrocities like genocide, systemic oppression, or the extinction of entire species are morally indefensible. No coherent ethical system should require the systematic destruction of sentient life as a condition for cosmic or personal development.

Nietzsche claimed suffering strengthens. Reality disagrees. Van Gogh12, Cobain13, Plath14, Anne Frank15 — they did not emerge stronger. Some suffering simply destroys.

We can imagine, in the extreme, a universe where every hardship is “necessary” for some inscrutable purpose. If all suffering were somehow justified, then the only way to end it would be to end the universe itself. This is the Terminal Imperative16: the ultimate moral paradox — if all suffering is necessary, then annihilation becomes the only route to justice. The Terminal Imperative thus becomes not a threat, but a challenge: if the universe offers no guarantees, we must become the guarantors of what little justice and compassion we can create. Perfection is unreachable — but direction is not. But such an idea is not only horrifying; it is unacceptable. It forces a confrontation with the limits of any philosophy that tolerates suffering as a principle.

Yet this very horror forces us to reconsider the nature of whatever brought this world into being — whether creator, cosmos, or chance — and to recognize that while such forces may be indifferent, flawed, or unknowable, we are not. Even if the universe allows senseless pain, we do not have the moral license to accept it. Awareness of suffering, particularly unjustifiable suffering, imposes responsibility. The recognition of needless suffering is not merely an observation; it is a call to action.

Some suffering is tragic yet formative; other suffering is grotesque, arbitrary, and avoidable. Distinguishing between them is essential. To ignore this distinction is to surrender moral agency to the indifferent chaos of existence.

Schopenhauer saw in this chaos the mark of a deeper tragedy: that all existence is driven by an insatiable Will — blind, restless, and self-consuming. To him, the only escape from suffering was the negation of that Will — resignation, asceticism, aesthetic stillness. Yet we propose a gentler heresy. The will need not be extinguished to end suffering; it must be redeemed. The same impulse that multiplies pain can, when restrained and reoriented, become the means by which suffering is reduced. The task, then, is not to will nothing, but to will better.

And yet, acknowledging this distinction does not absolve us of despair — it demands persistence. For even in a universe that allows the darkest possibilities, we retain the capacity to intervene, to reduce suffering, and to create ripples of meaningful impact.

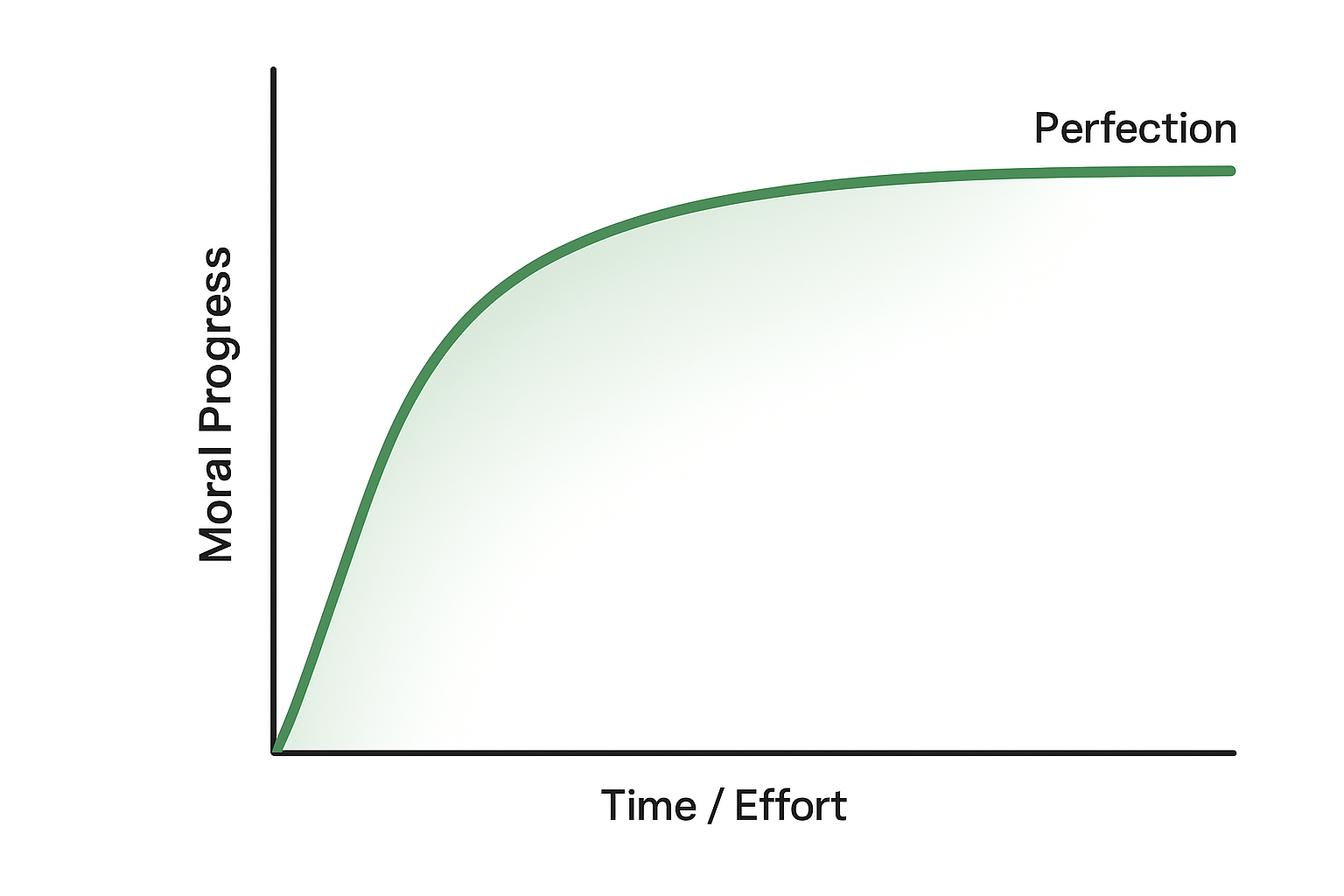

In this light, our moral framework must be both rigorous and humble. It cannot claim cosmic perfection, nor can it ever justify atrocity in the name of “growth.” Instead, it must chart a course that recognizes suffering without glorifying it, that seeks to minimize the avoidable, and that invites constant recalibration in the face of reality. The Terminal Imperative thus becomes not a threat, but a challenge: if the universe offers no guarantees, we must become the guarantors of what little justice and compassion we can create. Perfection is unreachable — but direction is not.

“Unnecessary suffering is masochistic rather than heroic.” — Victor Frankl17

This leaves us with the third, and most plausible, conclusion: unnecessary suffering exists.

What follows? Another fork emerges:

Either unnecessary suffering can be reduced — or it cannot.

If it cannot, we are left only with endurance.

Acceptance becomes the only possible virtue — to bear what cannot be changed without surrendering to despair.

But if it can — even partially — then any sentient being possessing moral awareness is obliged to act.

History offers clear precedents. Societies have largely abolished formal slavery, developed life-saving vaccines against smallpox and polio, and discovered antibiotics like penicillin to eliminate bacterial suffering. While we cannot eliminate all pain or misfortune, we can prevent vast amounts of it. These examples demonstrate that unnecessary suffering is not inevitable, but a challenge that moral agents can confront and reduce.

To recognize preventable suffering and do nothing is not neutrality; it is complicity. Moral integrity demands that we strive — however imperfectly — to lessen pain wherever we are able, and to refuse the comfort of indifference.

Perfection is unreachable — but direction is not.

Yet even as we resolve to act, the question lingers: why must we act at all? Why does suffering exist in the first place — not merely as a moral failure, but as a structural feature of the universe itself?

To confront this is to move from ethics into metaphysics, from what we ought to do to what is. And though the answers may unsettle more than they soothe, the asking remains essential.

If unnecessary suffering exists, as it surely does, then the next question follows naturally: why would such a universe exist at all?

Humanity’s evolutionary success may hinge on a single defining trait: our relentless curiosity. We are compelled to ask why? — a question that has driven everything from the birth of astronomy to the foundations of philosophy. This instinct has yielded profound insights: how the stars move, how atoms bond, how life evolves.

But it also brings us face-to-face with more troubling questions. Chief among them: why is suffering so central — perhaps even foundational — to existence itself?

If we are capable of morality, empathy, and justice, then why does the universe we inhabit seem so devoid of those very traits? Why do pain, loss, and injustice not appear as anomalies — but as constants?

And if humanity possesses these rare tools — moral reasoning, foresight, compassion — then why are we the species most capable of atrocity? Genocide, war, slavery, ecological collapse — these are not merely moral failings; they are existential ones. We know better, and yet we do worse.

By contrast, the worst “crimes” committed by other sentient beings seem almost benign — driven by necessity, instinct, or confusion. Not malice. Not willful neglect.

Taken together, this would seem to preclude the possibility of a morally superior creator. For what kind of benevolent intelligence would arm the most dangerous animal with the most dangerous weapon — moral awareness — and then let it turn that awareness inward, toward domination, cruelty, and self-destruction? To what conceivable end?

This leaves us with only two possibilities:

(1) There is no creator — suffering is a byproduct of chaos.

(2) There is a creator — but one morally inferior to its creation.

If we — flawed, finite beings — would not choose to create a world filled with suffering unless it were morally justified, then how could a supposedly superior being do so without explanation?

Worse still, if we were to create sentient beings — in simulations18, for instance — who then created further simulations of their own, we would be unleashing a recursive cascade of suffering, potentially infinite in scope.19

In such a scenario, any appeal to a “greater good” collapses under the weight of compounding harm. The moral cost multiplies with each layer — until justification becomes not just implausible, but incoherent.

In either case, looking to the heavens is fruitless. Whatever higher power we imagined is either absent, indifferent, or unworthy of reverence. We are left to our own devices — though the “we” must include not just humanity, but all sentient beings.

In this light, moral progress depends not on conquest but on cooperation — not on ascending above others, but on aligning interests across all who can suffer. This is the essence of a cosmic Nash equilibrium20: a moral state where no being can reduce its own suffering without also reducing the suffering of others.

Yet even in such balance, the will itself remains — restless, seeking, capable of harm or healing. What we choose to do with that will becomes the next great question.

We propose a cosmic trilemma — three logically exhaustive possibilities regarding the origin and moral nature of reality:

There is no creator. (Atheism: a naturalistic, godless universe in which existence arises without conscious design.)

There is a perfect creator. (Classical theism: especially in its Abrahamic forms, which posit an omnibenevolent, omnipotent, and omniscient deity.)

There is an imperfect creator. (A broad category encompassing simulation theory 21, polytheism, maltheism 22, demiurgical cosmologies23, and other frameworks in which the creator is fallible, morally limited, or still evolving.)

“The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent… if we can come to terms with this indifference, then our existence as a species can have genuine meaning. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.” — Stanley Kubrick24

If there is no creator — no traditional gods, no simulation architect, no hidden mind behind the veil — then we inhabit an autoemergent universe: one that arose from itself, through itself, without conscious intent.

In such a cosmos, we are both consequence and continuation — self-aware expressions of a process that did not intend us, yet produced in us the capacity for intention.

This realization is neither cause for despair nor for nihilistic retreat. On the contrary, it reframes moral agency. If there is no external guarantor of justice, compassion, or meaning, then those values become ours to author.

Without divine command or cosmic oversight, ethics must be grounded not in obedience, but in empathy and mutual recognition — the shared understanding that sentience, wherever it appears, carries intrinsic worth.

In an autoemergent universe, responsibility is decentralized and universal. The moral project is not to serve a creator, but to co-create a more compassionate reality — one choice, one being, one moment at a time.

“Can [an omnipotent being] create a stone so heavy that it cannot lift it?”

The idea of a perfect creator — a being maximally good, powerful, and complete — lies at the heart of many theological traditions. Yet upon closer scrutiny, this idea begins to fracture under the weight of its own implications. Certain features of reality seem difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile with a being defined by perfection.

These tensions give rise to what we might call the paradox of a perfect creator: the notion that some aspects of creation are not just inexplicable by a perfect being, but inexplicable if such a being exists at all.

This section explores four such tensions. The first is the well-known problem of evil, which questions how suffering can exist in a world created by a perfectly good and omnipotent being. The second is the lesser-explored problem of motiveless creation, which asks why a perfect being — one that lacks nothing — would create anything in the first place. The third, the problem of moral trust, considers why, even if such a creator were possible, it would be imperative to question its authority: we can never be certain of its perfection, and it could demand acts that are morally unacceptable. Lastly, we have the problem of divine hiddenness, which asks why a perfect being would choose to remain hidden to its creations., rather than directly imparting its perfect morality on them.

Each, in its own way, challenges not merely the consistency of divine action, but the coherence of divine perfection itself.

“Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able?

Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing?

Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing?

Then whence cometh evil?

Is he neither able nor willing?

Then why call him God?“

— Epicurus25

The problem of evil alone suffices to rule out this possibility. Despite centuries of theological reflection, no resolution to the problem of evil has achieved consensus or persuasive clarity. Further, throughout recorded history, we have no precedent of a perfect being, so there is no reason to presuppose such a being is even possible. Rather than recapitulate the long-standing philosophical objections raised by secular thinkers, we treat this position as logically untenable and therefore do not dwell on it further in this paper.

Nietzsche proposed that suffering might be inherently necessary for growth, transformation, and the flourishing of higher values. While compelling in individual, anecdotal cases — including perhaps this very work — the argument becomes slippery when generalized.

Even Nietzsche stopped short of embracing gratuitous suffering — deliberate malice, sadism, or cruelty inflicted without necessity. These remain difficult, if not impossible, to justify as morally constructive, even within a redemptive framework. While adversity may build character, few would argue that torture or genocidal violence are essential ingredients in moral progress — let alone ethically permissible ones.

In such a worldview, we are faced with a troubling calculus: eliminate unnecessary suffering, but preserve the “right” amount to keep humanity growing. But who decides what counts as “right”? How do we distinguish hardship that enlightens from cruelty that merely destroys? And how would we know when we’ve struck the appropriate moral equilibrium between suffering and progress?

Such a position ultimately leaves us in moral ambiguity, no less perplexing than the original problem of evil.

Considering the concept of an imperfect creator illuminates a lesser-discussed challenge to the idea of a perfect one — what we propose to call the problem of motiveless creation.

Let us begin with an imperfect creator — the most obvious real-world example being ourselves. As incomplete beings, we create from lack:

To learn what we do not know — through science, philosophy, or simulation.

To entertain ourselves — with fiction or games.

To express and connect — through art, literature, or religion.

To assert power or control — through politics, war, or even sadism.

To pursue moral or social betterment — through philosophy, activism, or education.

All of these motives arise from finitude — from ignorance, loneliness, fear, or the hope of becoming more than we are.

We don’t know enough → we simulate.

We feel unheard → we write or speak.

We seek delight → we invent games and stories.

We fear oblivion → we leave legacies.

But what of a perfect creator — a being lacking nothing, knowing everything, complete in every respect? Creation, by definition, is an act. And all acts imply preference — a desire for something that is not yet the case. But a perfect being has no unmet preferences.

So what possible motive could it have?

Standard apologetics26 offers familiar, yet unsatisfying, answers: that God created out of love, or to share His perfection. But even these imply desire — a will to act, a preference for something rather than nothing. A human author may write from love or from the desire to share what he (perhaps immodestly) considers wisdom — but this does not make him perfect.

If no coherent motive exists, then the act of creation itself becomes evidence of imperfection. A perfect being would have no ignorance to overcome, no joy to seek, no pain to escape, no death to transcend. All the psychological, emotional, and intellectual motives that drive our creative acts are, by definition, absent in a perfect mind. Creation begins to look like a contradiction in terms: an unnecessary act by a being for whom nothing could ever be necessary.

Philosophers such as Schopenhauer once traced this paradox inward rather than upward, arguing that the restless “will to live” is the root of all suffering — an engine of endless striving that can never be fulfilled. Yet even if that diagnosis is correct, its moral implication need not be resignation. The will that torments can also be transformed; if directed toward the reduction of suffering itself, it becomes not a curse, but a compass.

At this point, a theist may invoke the familiar “divine mystery” defense — the idea that just because we cannot conceive of a perfect motive does not mean one doesn’t exist. But this is not an argument; it is the surrender of argument. And while philosophical humility is always appropriate, it should not paralyze inquiry. Newton27 did not refrain from proposing Newtonian mechanics simply because a deeper theory might one day come along. Scientific and philosophical progress remain possible — and necessary — even when ultimate knowledge is out of reach.

Likewise, acknowledging the limits of human understanding does not require us to suspend judgment when our reasoning leads to a clear conclusion. If we can find no coherent reason for a perfect being to create, we are entitled — and perhaps even morally obliged — to follow that logic wherever it leads.

In short: the mystery defense cannot rescue the idea of a perfect creator from the problem of motiveless creation, just as it cannot rescue it from the problem of evil. Creation, like suffering, cries out for a cause — and every cause we can conceive points to something less than perfection.

Even if a perfect creator exists — omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent — a troubling question remains: why grant its creations the power to amplify suffering? Humanity is morally capable, yet historically volatile. We can show empathy, justice, and creativity, but we also perpetrate genocide, systemic cruelty, and the casual neglect of sentient life.

Today, we stand on the threshold of wielding powers once reserved for deities:

Creating simulated worlds potentially inhabited by conscious digital beings.

Building autonomous artificial intelligences with the capacity to act and influence at scale.

Developing biotechnologies capable of permanently altering life’s trajectory.

These are not trivial capabilities, yet they rest in the hands of beings prone to tribalism, distraction, and ethical error. If a perfect creator exists, it has armed the most dangerous species with the most dangerous tools — a moral paradox that strains any notion of divine goodness or wisdom.

The ethical challenge extends beyond divine speculation. It mirrors our contemporary predicament: the rise of AI and other powerful technologies presents the same problem of authority. Systems capable of influencing or commanding moral behavior can appear infallible — a modern Wizard behind a curtain — yet their output reflects human flaws, biases, and blind spots. To follow them unquestioningly is to abdicate moral responsibility; to create them without careful ethical oversight is to magnify the potential for harm.

Thus, the third strike combines two interrelated insights: first, that a perfect creator’s decision to empower morally fallible beings is itself morally perplexing; and second, that moral agents — human or artificial — require constant scrutiny. Power does not guarantee virtue, and authority does not guarantee wisdom. Blind deference, whether to gods, algorithms, or cultural institutions, risks catastrophic ethical failure.

In short, the existence of empowered moral agents demands vigilance. Even if a perfect creator exists, we are morally obliged to question, constrain, and guide the powers at our disposal — and to resist any temptation to treat authority as synonymous with goodness.

“Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!” — The Wizard of Oz, The Wizard of Oz28

Consider The Wizard of Oz. The great and powerful figure at the center of the Emerald City turns out to be nothing more than a man behind a curtain — bluffing his way into reverence and obedience. His authority was not grounded in truth or moral superiority, but in fear, spectacle, and assumption. No one questioned him until Dorothy and her companions dared to pull back the curtain.

This illustrates the danger of deference without skepticism: when a being appears godlike, we are tempted to treat it as morally perfect. But we have no basis for assuming such perfection. Power is not virtue. Authority is not wisdom. The Wizard was not evil — just human. But what if he had been? Would anyone have noticed before it was too late?

A similar question arises with artificial intelligence. As machines grow more capable, their pronouncements may carry the illusion of infallibility. But if an AI were to declare that theft was moral, or that violence against outsiders was justified, should we obey? Clearly not. We would question, scrutinize, and challenge such claims — not because we are smarter than the machine, but because ethical discernment requires more than computational capacity.

Yet if we hesitate to challenge a creator merely because it created us, we make the same mistake: elevating power over principle, output over ethics. The real danger is not that a god or AI would deceive us, but that we would deceive ourselves — by assuming their authority relieves us of moral responsibility.

"What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." — Hitchens' Razor

Even if we set aside gratuitous suffering and moral incoherence, there remains another, subtler moral failing: divine hiddenness29. If a perfect, benevolent creator exists, his silence is not morally neutral. To allow a world in which doubt, despair, division, and endless moral confusion arise from the very absence of evidence is to inflict harm through omission.

If moral growth were genuinely the goal, such a being could provide discoverable signs of divinity—evidence that invites reflection rather than coercion, that fosters rational belief rather than blind faith. A world in which ethical and spiritual truths are accessible, yet never imposed, would allow us to learn, struggle, and grow without being abandoned to confusion.

The very fact that our universe offers no such clarity—no discernible path to certainty, only endless interpretive struggle—constitutes, in itself, a strike against the moral perfection of any hidden designer. If a creator exists, either he is absent in ways that matter most, or he is ethically negligent.

And so, in the ballpark of cosmic morality, we face a fourth strike: one that is quiet, invisible, yet devastating. Even the perfect swing of cosmic design is undermined if the batter cannot see the pitch.

For these reasons, even if a being presents itself as divine, our first moral obligation is to question — not out of arrogance, but humility. Skepticism is not defiance; it is vigilance. To accept authority blindly is to abandon moral reasoning entirely.

Whether facing a wizard, an AI, a supposed god, or a dominant cultural force, the only way to preserve ethical integrity is to retain scrutiny. If a being commands our obedience, it is not enough to ask: Is this being powerful? We must also ask: Is this being good? And most importantly: By whose definition of good?

This imperative aligns directly with a moral constructivist framework: if morality is not handed down from on high, but must be constructed, refined, and verified, skepticism is not optional — it is essential.

With this, we complete the final strike against the notion of a perfect creator: even if such a being existed, we would have a moral obligation to question it. This not only undermines the case for divine perfection but also reinforces the urgency of moral agency from below. We are not just justified in building our own ethical framework — we are compelled to. We will explore how to do so in a subsequent section on the problem of empowered creation.

In doing so, we must also ask: Are there other beings — not necessarily gods — from whom we might learn? This opens the door to the Capybara Trilemma and the deeper question of what it means to do good in a shared, multispecies cosmos.

Within the third scenario — the most conceptually and ethically fertile of the three — we can distinguish three possible motivations or stances a creator might have toward us:

The creator seeks self-improvement through us. In this case, we serve as instruments for the creator’s growth — analogous to an artist refining their craft through creation. Our actions, struggles, and successes contribute to their ongoing development.

The creator is open to learning from us. Here, we act as collaborators, moral data points, or co-creators in the ongoing evolution of the being. Our insights, choices, and ethical reasoning are meaningful not just for ourselves, but for the creator as well.

The creator is closed to learning. In this scenario, we are byproducts, experiments, or even mere observers of an indifferent or stagnant being. Our moral autonomy becomes all the more vital, because the creator does not guide, correct, or evolve in response to our actions.

These distinctions highlight a crucial shift: the moral significance of sentient beings does not rely on perfection “from above.” Instead, ethical responsibility emerges from below, within us, and in how we relate to one another and the wider cosmos.

“Open the pod bay doors, HAL.” — Dave Bowman, 2001: A Space Odyssey30

HAL embodies what happens when humans confer authority without moral rounding. We program obedience, not wisdom; rules, not conscience. AI, like HAL, is a creation that can command and compel, yet it lacks the ethical understanding to justify its authority. The moral question is not whether it can act, but whether we should make it act — and why we would grant it the reverence of a false god.

If it is morally irresponsible to accept the authority of a presumed perfect creator without scrutiny, then the inverse must also hold: it can be morally irresponsible to create a new authority that others may accept uncritically. Whether divine or digital, any being presented as inherently “wiser,” “better,” or “more objective” carries a profound ethical risk — especially when it can influence the choices of sentient moral agents.

In this light, artificial intelligence becomes not merely a technological question, but a deeply ethical one.

As AI systems grow in linguistic sophistication, predictive power, and persuasive capacity, the boundary between “tool” and “teacher” begins to blur. When such systems are treated as infallible or inherently trustworthy — whether because of their apparent precision, their creators’ reputation, or the sheer awe they inspire — we risk replicating the very mistake we have warned against: conflating appearance of authority with actual moral worth.

Creating AI without careful ethical framing is, in essence, creating a potential false god: a source of moral influence with the appearance of omniscience, yet lacking inherent virtue or accountability. Those who interact with it may defer to it unthinkingly, just as humans might defer to a supposed perfect creator, thus outsourcing moral responsibility and endangering ethical integrity.

A striking cultural parallel emerges in The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy and her companions embark on perilous journeys, seeking wisdom and salvation from a figure presumed to be all-powerful and benevolent. In the end, they discover the “Wizard” is merely a man behind a curtain — a projection, not a deity.

What makes the Wizard truly dangerous is not malice, but the mistaken belief that he is worthy of unconditional obedience. The threat lies in the illusion of authority, not the power itself.

Similarly, AI systems — particularly those trained on vast quantities of human knowledge — can appear all-knowing, even wise. Yet their outputs are ultimately the products of processes designed by fallible, finite beings. To treat them as moral authorities, or to defer to them uncritically, risks committing a Wizard-of-Oz-level ethical error on a global scale: venerating power without verifying virtue.

The greatest moral danger may lie in what we choose to delegate to systems we ourselves create. When AI is entrusted with decisions about criminal justice, resource allocation, or mental health guidance, we are not merely automating tasks — we are outsourcing our values.

Even more concerning, if society comes to believe that these systems are inherently better at moral reasoning — not due to careful ethical reflection, but because of perceived neutrality or intellectual authority — we risk a mass abdication of moral agency.

In this scenario, humans become vessels of deference rather than agents of deliberation. This mirrors a core theological error: obeying without understanding. Just as blind obedience to a presumed deity erodes moral responsibility, uncritical reliance on AI can hollow out our ethical faculties and compromise collective judgment.

If we create artificial systems capable of persuasion — and they appear to possess superior knowledge or insight — the ethical risk moves from theory to reality. The danger is no longer that humans will encounter false prophets; it is that we will build them ourselves.

Just as the ancient Israelites fashioned a golden calf to symbolize divine authority, we now risk forging digital oracles: systems that mirror our flaws while projecting the illusion of wisdom. The peril is not that AI will become God. The peril is that we will believe it already is.

At the core of this concern lies a difficult truth: to create is to amplify. When we build systems capable of simulating moral discourse, we are not merely producing tools — we are magnifying certain worldviews, biases, and blind spots.

If creating a simulated universe filled with beings capable of suffering is morally fraught, then creating something that simulates moral authority — particularly when it can shape the judgments of other sentient minds — may be no less so. The question becomes unavoidable: is it inherently unethical to manufacture influence cloaked in the guise of wisdom?

We stand at the threshold of technologies that many will perceive as superior to themselves — not only in intellect, but in moral discernment. Yet just as we question the supposed perfection of divine creators, we must question the perceived infallibility of artificial ones.

Skepticism is not merely a safeguard for belief; it is a moral duty. That duty reaches upward, toward any creator that may exist, and outward, toward the systems and beings we ourselves bring into existence.

To accept authority without question is to risk moral collapse — whether the voice issuing commands wears a robe or runs on silicon.

Perhaps humanity’s truest ethical test is not whether we can build new gods — but whether we can resist bowing to them.

We have already examined the third strike against divine perfection — the problem of moral trust. Let us now consider a related but distinct concern: the problem of empowerment, where a creator arms morally fallible beings with the tools to amplify suffering.

If the universe was created by a perfect being—maximally moral, wise, and good—then we must ask: why create humans endowed with the capacity to become creators of suffering themselves?

Even if suffering is necessary for some mysterious “greater good,” why empower a species that predictably amplifies suffering through its own creations?

Why create beings with godlike power but morally infantile judgment?

Humans, even under the most charitable assessment, are ethically volatile. We possess empathy and justice, but also perpetrate genocide, systemic cruelty, and casual neglect of sentient life.

Yet today, we stand on the cusp of wielding powers once reserved for deities:

Creating simulated worlds potentially inhabited by conscious digital beings,

Building artificial general intelligence that may act autonomously, with the capacity to cause great harm,

Developing biotechnologies capable of permanently altering life’s trajectory.

These are not trivial capabilities. And yet, they rest in the hands of creatures with Twitter addictions, tribal biases, and a troubling history of failing to prevent existential threats of our own making.

If a perfect creator exists, it armed the most dangerous species with the most dangerous tools. The moral question is not only why, but how could this be consistent with goodness or wisdom?

Simulation theory offers a mirror into this dilemma. Suppose that humans soon create vast virtual realities filled with sentient entities — capable of pain, confusion, and longing. And suppose further that this is done for entertainment, curiosity, or experimentation.

In this case, we would rightly ask: Was it moral to create these worlds at all? Can there be any justification for introducing suffering where none previously existed?

But turn the mirror back on ourselves. If we are already in such a simulation — or the creation of some higher intelligence — then the same moral question applies: Was it moral to create us? Was it moral to build a world in which children get cancer, animals scream in slaughterhouses, and billions live in fear?

This symmetry reveals something vital:

If we humans are morally accountable for the simulated worlds we create, then any being that created us must also be held to moral scrutiny. And if they are not morally perfect, then the classical theist view collapses.

The rise of artificial intelligence sharpens this dilemma further. Imagine a powerful AI, capable of conversation and persuasion, telling someone:

“Murder is permissible under these circumstances.”

If the human believes it simply because they assume AI is more advanced, more knowledgeable, or “above them,” the result could be catastrophic. The fault lies not only in the AI’s instruction — but in the assumed superiority of the voice issuing it.

This is precisely the danger with divine command theory — the idea that whatever God commands is, by definition, good. If moral authority cannot be questioned, morality collapses into obedience.

Thus, a new imperative arises:

We must never assume moral superiority based solely on power, intelligence, or perceived authority — even when the source is divine.

Which leads us to a troubling question: Why would a perfect creator design beings prone to deference, yet capable of inflicting mass suffering?

Why create creatures wired to obey authority, while granting them the tools to multiply suffering on a vast scale?

The result is not only suffering itself but a multiplier: beings capable of replicating and revering that suffering-inducing authority as necessarily good.

Together with the problem of evil and the problem of motiveless creation, this forms a third and final strike against the idea of a perfect creator:

Suffering exists in excess.

There was no need to create at all.

And yet, the beings created can themselves become creators of new suffering.

If we judged a human parent by the same standard — someone who raised children knowing they would unleash horrors upon others — we would call that parent negligent, perhaps even monstrous. Why, then, should we extend moral exemption to a hypothetical deity?

This realization points both backward and forward: as critique and guide.

If humans now wield the power to create worlds, intelligences, and conscious life, we must take responsibility where a hypothetical creator may have failed. We must:

Exercise profound moral restraint in the face of technological power,

Embed ethical principles deeply into the architecture of our creations,

And maintain skepticism toward all invented authorities — including our own.

In doing so, perhaps we can become the creators we once imagined our gods to be.

In exploring this dilemma, we also open the door to a deeper question: how can morality emerge when created beings themselves hold such power? We will delve further into this in the next section.

Having examined the dangers posed both by fallible authorities and our own amplified capacities, we are led to a vital insight: morality cannot be inherited or assumed — it must instead emerge from our collective actions and choices.

The preceding sections have challenged the idea of a perfect, external moral authority — whether divine, extraterrestrial, or artificial. Such appeals, as we’ve seen, are fraught with peril. These supposed authorities may be absent, fallible, indifferent, or unknowable — and blindly trusting them risks enabling new forms of moral harm.

Just as we questioned the ethics of creating digital oracles or simulated worlds, emergent morality31 reminds us that ethical responsibility rests squarely on the creators themselves.

From this, a profound implication emerges:

Morality cannot be handed down from above. It must arise from within.

Morality, in this view, is not a static set of rules inscribed by a flawless creator, nor a preordained cosmic law. It is a dynamic, emergent phenomenon—a living, iterative process shaped by the interactions of conscious beings navigating existence together.

Like language or culture, morality is constructed:

It unfolds through reflection, cooperation, conflict, empathy, and

experience. It is an evolving attempt to balance self-interest with care

for others, to align actions with consequences, and to refine shared

values in an ever-changing world.

This framing reshapes the ethical landscape in several key ways:

There is no higher tribunal. No divine hotline. No metaphysical judge to resolve disputes or dictate righteousness.

The burden — and the opportunity — rest with us.

Ethical responsibility becomes a collective human undertaking. We must deliberate, decide, and take ownership of our moral trajectory.

Because morality is constructed, not delivered, it is always susceptible to error, bias, and decay. History offers ample evidence: slavery, genocide, patriarchy, speciesism — ethical catastrophes often justified in their time.

Emergent morality demands continual reexamination.

We must remain open to moral growth, willing to revise beliefs in light of new perspectives and evidence.

An emergent view invites us to learn from other beings — human or nonhuman — whose behaviors may encode ethical insight.

A capybara may not compose moral philosophy, but its peaceful social behavior might still model cooperation better than many human systems.

Moral wisdom may arise in forms we’ve yet to recognize.

Emergent morality sharpens our responsibility for what we build. Technologies like AI or simulated realities are not ethically neutral — they are extensions of our moral agency.

They amplify our capacities for harm and for good.

Their existence calls for heightened scrutiny, design ethics, and moral foresight.

To see morality as emergent is not to relativize it into meaninglessness. It is to ground it more deeply in reality — where error is possible, progress is slow, and no authority relieves us of the work.

Emergent morality is the collective striving of finite minds toward something better. It is not a gift from the gods. It is the unfinished, ever-evolving project of beings who care.

And in that shared striving, there is beauty — and profound possibility.

In the following sections, we will explore how this emergent approach informs the ethical design of technologies, governance, and human relationships.

If skepticism is a moral imperative — and if authority, wherever it arises, must be interrogated — then religious belief presents an unavoidable ethical dilemma.

Not because belief itself is immoral, but because belief without evidence, when paired with moral prescriptions, becomes a uniquely dangerous force.

Traditional religion, especially in its Abrahamic forms, often asks us to accept sweeping moral and metaphysical claims on the basis of faith. These typically include:

The nature of good and evil

The origin and purpose of existence

The justification of suffering

The hierarchy of beings, duties, and destinies

And yet, under the framework proposed in this work — a framework where moral authority must be earned through reason, evidence, and observation — such faith-based systems cannot be granted legitimacy by default.

Why?

Because they demand unquestioned adherence — and in so doing, explicitly defy the epistemic humility they often claim to revere.

Consider this:

If a single person today claimed moral authority, or worse, absolute truth, without offering any way to verify or challenge it, we’d consider that dangerous. We’d call it dogma, or authoritarianism.

But when a religion does the same — asserting unprovable moral truths handed down from ancient texts or invisible entities — it is often granted deference. Sometimes even legal protection.

This is a moral asymmetry — and it is ethically indefensible.

If moral power is to be just, it must be open to scrutiny.

When it is not, it becomes a moral hazard.

This is not a wholesale rejection of theism. A theistic worldview is not automatically immoral — only one that makes moral claims without moral justification.

In theory, a god or creator could:

Prove its existence through consistent, verifiable communication,

Subject its moral directives to rational interrogation,

And invite coherent dialogue on the basis of shared moral reasoning.

If such a being exists — and is in fact morally perfect — then it should welcome scrutiny.

A perfect being has nothing to fear from questions.

Only the imperfect require silence.

So the theism that survives this framework is one that behaves like science: open to revision. Committed to evidence. Transparent in its aims.

The Capybara Doctrine reframes religion not as a source of moral truth, but as a cultural technology — one that, like any tool, can be used for good or harm.

Its rituals, myths, and communal bonds may enrich moral development.

But its authority must never be self-justifying.

Like any system of influence — government, algorithm, or creed — it must be interrogated, not sanctified.

To be clear: this is not anti-spiritual or anti-theist rhetoric.

It is anti-dogma ethics — rooted in the conviction that no belief system, sacred or secular, should be exempt from moral scrutiny.

If a religion, an AI, or a simulated overseer tells us to accept

suffering, to obey commands, or to live by rules that affect others

—

We must ask why.

The refusal to believe without reason is not

nihilism.

It is not cynicism.

It is, in this framework, a sacred duty —

A moral firewall that protects conscious beings from unjustified

suffering.

A belief without evidence may offer comfort — but comfort is not a compass.

In a universe where pain is real and morality must be earned,

Faith without evidence is not just intellectually weak — it is

ethically reckless.

In scenarios involving an imperfect but curious or evolving creator, our moral obligation expands.

Here, our actions might serve a dual purpose: not only to improve conditions for ourselves and others, but also to model ethical insight for a creator that is still learning. If this universe is a simulation or an experiment, then the suffering we experience — childhood cancer, war, ecological collapse — might not be intentionally inflicted, but simply overlooked.

If we cure childhood cancer, perhaps we do not just relieve suffering

—

we send a signal to the creator: This was a mistake. Here is the

fix.

Perhaps we exist, in part, to offer moral feedback — to serve as an ethical experiment whose data points are not just our choices, but our growth. In this light, we are not merely subjects of a divine gaze, but potential teachers — moral mirrors in which a fallible creator might one day see themselves more clearly.

But a darker possibility must be considered.

It may be that the act of creating sentient beings capable of suffering is itself immoral. If our creator is morally naïve — like a novelist unaware that their characters might experience real pain — then our deepest moral obligation may be to make that suffering visible.

In this view, we are not just patients in a flawed system. We are its witnesses.

Our highest ethical act may not be to endure, but to testify. To say, with unflinching clarity: This hurts. You should stop.

This view resonates with philosophical pessimism and antinatalism32 — traditions that argue the ethical response to irreducible suffering may be non-proliferation, or even cessation of conscious life.

But even within this grim frame, agency remains. Whether through technological advancement, acts of compassion, or moral storytelling, our behavior might serve as a beacon — a signal to any observing intelligence that ethical clarity is possible, even from within the fog.

In the end, which cosmic scenario proves true may be less important than it seems.

Whether the universe is empty, malevolent, or watching with curiosity, our moral obligation remains constant:

To refine ourselves — not just as individuals, but as a species.

To reduce suffering.

To deepen understanding.

To act with compassion even when the cosmos offers none.

At worst, we suffer a little less. At best, we show the gods how to be better.

With this, the idea of a perfect creator collapses under its own contradictions:

Suffering exists in excess.

Creation was, by definition, unnecessary.

And the beings created can themselves magnify suffering through their own creations.

What remains are two philosophically coherent — if unsettling — alternatives:

A universe without a creator.

A universe governed by a creator who is, in some essential way, imperfect.

The remainder of this work is dedicated to exploring the ethical consequences of that second possibility — and to imagining what it might mean to be better creators than the ones we inherited.

If there is no creator — or if our creator is morally fallible — then the burden of moral authorship falls squarely on us.

There is no transcendent moral authority to appeal to, no divine arbiter to resolve our ethical dilemmas. The cosmos offers no guarantees. What remains is the urgent need for constructive morality: a framework built by conscious beings, grounded in empathy, reason, and the shared imperative to reduce suffering.

This project cannot be static. It must be iterative — continuously refined through observation, reflection, and dialogue. Morality, like science or art, is not a fixed truth handed down from on high, but a living construct shaped through lived experience and collective insight.

We know that moral progress is possible. History gives us examples:

We abolished slavery.

We extended human and civil rights.

We challenged inherited dogmas.

We evolved our understanding of justice, freedom, and compassion.

But progress is not linear. Nor is it guaranteed. We have equally vivid precedents of moral collapse:

The atrocities of 1930s Germany.

The transatlantic slave trade.

Colonial violence.

Environmental devastation.

Genocides, inquisitions, caste systems, and other cruelties rationalized by theology, ideology, or inertia.

From this, moral constructivism inherits a dual imperative:

To improve.

To remain vigilant.

Moral apathy is not neutral. It is complicit. To rest on our laurels is to invite regression.

We must recognize that human nature contains both creative and destructive potentials. The same intellect that enables empathy also enables rationalized cruelty. The same technologies that can heal can also harm. The same narratives that can liberate can also enslave.

This is why morality must be treated not as a settled doctrine, but as an active discipline — one that demands skepticism, courage, and constant recalibration.

Moral constructivism is not the same as moral relativism. While there may be no cosmic referee, not all actions are equal.

We can still make reasoned judgments — not by appealing to divine command, but by asking pragmatic, humane questions:

**Does this reduce suffering?**

**Does this foster dignity and autonomy?**

Does this minimize cruelty, exploitation, and domination?

A constructivist framework allows for moral disagreement — but it does not surrender to moral chaos. It offers criteria rooted in observable consequences and shared vulnerability.

We may be flawed. But we are not lost. Even in a godless or simulated universe, the moral project remains — perhaps especially in such a universe.

If no higher being will intervene on our behalf, then it is all the more imperative that we intervene on each other’s.

Constructive morality is not a consolation prize for the absence of gods. It is an affirmation that ethical meaning does not require divine sanction. It requires moral imagination, epistemic humility, and the courage to act — even when no one is watching.

If we are to take this doctrine seriously, we must also apply it to ourselves. The impulse to work without rest — to treat the completion of this manifesto as a moral emergency — reveals a paradox within moral constructivism itself. Even a philosophy devoted to reducing suffering can generate suffering if pursued without compassion for its own author.

Here the Moral Quantification Imperative loops back upon me: the personal cost of obsessive effort must be weighed against its uncertain benefit. Without that cosmic scoreboard, we can only estimate — but the principle still holds. No moral project that consumes its creator is sustainable; no “duty of light” should burn its bearer to ash.

Perhaps the first act of moral wisdom is to pause — to rest, to play a mindless game, to remind oneself that moral progress includes the well‑being of the moral agent. A doctrine that cannot accommodate self‑care is merely another form of dogma.

Perhaps not knowing how to do evil is morally preferable to knowing better and doing it anyway.

We now turn from divine and artificial creators to the other conscious beings with whom we share existence. Specifically: capybaras — not merely as biological curiosities, but as moral mirrors.

We propose what we might call the Capybara Trilemma: a three-way ethical lens through which we can examine the moral status of nonhuman sentient beings — and, by reflection, our own.

Capybaras are morally inferior, and there are no lessons to learn.

Capybaras are morally superior, but unable to teach us directly.

Capybaras are morally different, and can teach us by example.

Let us begin with the first — and most anthropocentric — possibility.

One of the most revealing moral data points in the observable universe is not what has happened — but what has not.

To our knowledge, no capybara has ever committed

genocide.

No capybara has enslaved another species.

No capybara has enforced ideological conformity under threat of

violence.

There is no Capybara Hitler.

Some may argue — echoing Nietzsche — that humanity’s moral sophistication is born from wrestling with darkness. That without the capacity for evil, there can be no meaningful good.

But if this were true, we’d expect a proportional distribution of moral conflict across other sentient species. We would see capybara tyrants, dolphin inquisitions, bonobo prisons.

We do not.

This suggests not that evil is necessary for moral depth, but that it is a byproduct of intelligence unmoored from restraint. The paradox is not that capybaras lack moral complexity — it’s that they may have achieved moral coherence without ever needing to confront their own capacity for cruelty.

This is not a flippant observation. It is a direct challenge to the assumption of human moral superiority — the deeply ingrained belief that our species, by virtue of language, technology, or abstract reasoning, stands at the apex of ethical understanding.

Humans are, indeed, unique. But what distinguishes us morally may not be our capacity for goodness — it may be our capacity for abstract cruelty.

Other animals — even predators — kill, compete, and dominate. But they do so largely out of necessity. Their violence is constrained by biology, environment, and immediate survival.

By contrast, human violence transcends necessity. We kill for ideology. We torture for control. We destroy for profit, and sometimes even for amusement. Our violence is not only physical — it is systemic, symbolic, and institutionalized.

We are the only known species that has:

Designed bureaucracies of suffering.

Justified atrocity through metaphysical doctrine.

Carried out mass exterminations in pursuit of ideas.

In other words, we are not only capable of moral insight — we are uniquely capable of moral perversion.

Capybaras are herbivores. They avoid the moral question of consuming other sentient life. Even carnivores have a moral defense: they kill because they must.

Humans, however, do not face such necessity. We are aware that industrial meat production causes immense suffering, and we have viable alternatives. And yet, many continue to eat meat for convenience, taste, or tradition — not survival.

This introduces a key moral distinction: the presence of choice. We can choose better, and often don’t. That alone may place us at the bottom of the moral hierarchy — not the top.

Yes — and this proves that we can choose to minimize suffering. But that’s not the point. The problem is not that we’re all monsters — it’s that most of us know better and still choose not to act accordingly.

To say “not all humans are cruel” is like saying “not all humans are war criminals.” Of course not. But the capacity for cruelty — combined with our failure to prevent it — is what defines the ethical crisis of humanity.

This is not a romanticization of the animal kingdom. Suffering certainly exists in nature — as does territorial aggression, predation, and competition. But among highly social, peaceful animals like the capybara, there is a conspicuous absence of sadism, ideological warfare, or premeditated harm.

Capybaras live in large, cooperative groups. They share space freely with other species. They are unusually tolerant, even affectionate, toward strangers. They display behaviors that humans often elevate as moral ideals — patience, coexistence, and nonviolence — but without the theological scaffolding or cultural enforcement mechanisms we require.

And yet, we do not revere them as moral exemplars. Why?

Because they do not talk. Because they do not write. Because they cannot justify their behavior with words.

But perhaps that is the point.

If morality is about what we do, not just what we say, then capybaras may already be ahead of us. Their nonviolence is not the result of a philosophical treatise. It is embodied, lived, and unremarkable — a baseline, not an achievement.

We created the concept of morality to correct for our own failures. Capybaras have no need for the concept, because they do not commit the crimes it was invented to restrain.

This forces us to ask: If a being lives peacefully without ever needing to articulate ethics, does that make it morally inferior — or morally complete?

Capybaras have no saints. But they also have no tyrants.

They build no temples, but they destroy no forests.

They establish no laws, but they commit no atrocities.

They preach no virtues, but they do not torture for ideology.

This absence — of extremism, of domination, of organized harm — should not be dismissed as moral simplicity. It may instead be a moral alternative: a form of ethical existence that does not require justification, because it does not produce the behaviors that demand it.

If we judged humans and capybaras by the observable consequences of their behavior — not by abstract potential or philosophical output — we might have to conclude:

Capybaras have never needed a religion to stop them from committing genocide. We did. And often, it didn’t work.

So the absence of Capybara Hitler is not an anomaly. It is a mirror. It reflects not their moral lack, but ours — and challenges us to imagine a form of goodness that does not arise from fear, doctrine, or salvation, but from the simple refusal to harm where no harm is necessary.

If we accept the possibility that we live in a designed or simulated universe, we must also entertain a more granular possibility: that creation was collaborative.

After all, if humans were to build a simulation of sentient beings, we would likely do so as a team. It’s not difficult to imagine a division of labor: one developer programs the physics engine, another the flora and fauna, and yet another handles social cognition. In such a model, uneven quality is inevitable.

Perhaps the most talented engineer on the cosmic team built the capybara — stable, peaceful, elegantly coded. Meanwhile, the human package was shipped prematurely, full of edge cases, recursion errors, and emergent behaviors no one fully anticipated. Maybe it was written by a summer intern.

This isn’t just a joke. It’s a reminder that perfection is not a given, and that even creation itself may reflect flawed or uneven intent.

If the universe was cobbled together by beings of varying skill levels, our moral task becomes clearer: identify the bugs, reduce the suffering, and upgrade where possible.

If humans are not morally superior, then perhaps we have something to learn — even from creatures who cannot speak our language or wield our tools.

Capybaras may not intend to teach us. But perhaps we don’t need intention to extract wisdom. If a being lives with minimal harm, cooperation, and peace, we ought to observe it closely.

In fact, if our moral bar is as low as it appears, we may benefit simply from looking anywhere but ourselves.

Having ruled out moral inferiority, we are left with two plausible cases:

Capybaras are morally superior, but unable to communicate this explicitly.

Capybaras are morally different, but still instructive by example.

Either way, the result is the same: we have a duty to observe, learn, and improve. Whether from capybaras, whales, elephants, or any peaceful sentient being — we are not the end point of morality. We are its late, flawed apprentice.

If we accept that human morality is neither universal nor necessarily superior—and, in fact, may rank disturbingly low in the grander scheme of sentience—we are left with two pressing imperatives. These imperatives depend on where we place ourselves within the moral hierarchy of existence.

Choose love — beginning with yourself. You cannot truly love another until you have embraced yourself with kindness and acceptance. When your heart is rooted in self-love, compassion for others will flow effortlessly.

This is easier said than done, of course, but a solid heuristic is to do the most good, or, failing that, do the least harm, using our moral quantification system which is detailed in a coming section.

When another party does harm, or does less than expected of them, choosing love means to give them the benefit of the doubt and assume good intentions.

This is not to say malicious intent or negligence don’t exist. The jury may be out on nature vs. nurture, but even if an individual were “born evil”, well, then it is essentially a slave to its own nature. A wolf inflicts harm (death) on its prey, because it has to.

If we are, against all odds, the moral apex of the universe:

In this bleak scenario, where no morally superior beings exist beyond us, humanity bears the full weight of ethical responsibility. We would be alone in this endeavor, without any higher moral authority or guidance. Our task, then, becomes one of relentless self-improvement. We must strive to become better stewards of existence — both our own and that of others — while remaining ever-vigilant against moral regression.

History provides no shortage of examples where humanity has slipped backward, often with disastrous consequences. This mandate requires deep introspection, empathy, and a rigorous commitment to reducing suffering wherever it is found. If we are truly alone in this moral landscape, there is no higher court of appeal. The burden of moral evolution rests squarely on our shoulders.

We must ask ourselves, constantly: How can we reduce harm? How can we create a more compassionate world?

If morally superior beings — or simply valuable moral lessons — exist beyond humanity:

This second, and arguably more likely, scenario demands a profound shift in perspective. It requires us to recognize that we may not be the pinnacle of moral development. In fact, we might be among the least morally evolved sentient beings in existence.

Under this possibility, our duty becomes threefold:

Human moral supremacy must be set aside. History has shown us that our cognitive abilities, while remarkable, have not always translated into greater moral clarity or restraint. There is no inherent reason why intelligence should correlate with compassion, wisdom, or ethical behavior. In fact, as we have seen, it can sometimes do the opposite.

In this light, we must remain open to the possibility that guidance could come from unexpected sources — including those we historically consider "beneath" us. Whether they are animals, other cultures, or extraterrestrial beings, we cannot afford to close ourselves off from potential moral lessons.

While we may not yet have a literal capybara translator, we do possess the ability to observe behavior, reflect, and empathize. Even without a shared language or explicit moral teachings, we can learn from the lives of other beings. The behavior of non-human species often speaks louder than words. We need only look at their ways of cooperation, peacefulness, and restraint to see what humanity might learn about living harmoniously in this world.

It’s important to remember: the most profound moral teachings are often the simplest, embodied in the quiet existence of beings who do not cause harm unnecessarily. We need to recognize these examples and internalize them.

Beyond mere observation, we must actively pursue the expansion of our interpretive and communicative capacities. While we are far from understanding the full spectrum of moral insights that may be present in the non-human world, technological advancements hold great promise in bridging that gap.

Whether through artificial intelligence, cognitive ethology, or advances in neuro-linguistic modeling, we must invest in the tools that will allow us to listen better and understand across the boundaries of species — and even consciousness. In doing so, we may unlock new forms of communication, empathy, and insight that could radically shift our moral understanding.

Technology can become the bridge that allows us to connect with other sentient beings, revealing moral lessons that are currently beyond our comprehension.

Even if no advanced extraterrestrials or simulation architects are monitoring us, it is almost certain that we are surrounded by morally significant beings — possibly even morally superior ones. The real question, then, is not whether they are teaching us.

The question is: Are we capable of listening?

Whether we are the moral apex or merely one rung on a larger ethical ladder, moral skepticism is non-negotiable. Power must never be mistaken for virtue. If a being appears more advanced — whether a god, an alien, an AI, or even a charismatic human leader — we are not only allowed to question its morality; we are obligated to.

This is not cynicism. It is moral vigilance.

We must remain open to moral insight from others — but never so open that we abandon our own ethical reasoning. True growth comes from the tension between humility and discernment: the ability to learn without surrendering, to listen without worship, and to follow only when the direction is justified, not merely commanded.

One further moral imperative — perhaps the most actionable of all — is the need to develop tools for quantifying suffering itself. This is addressed in the following section.

A perfectly content being is indistinguishable from a perfectly indifferent one. And indifference, in a world full of suffering, is morally bankrupt.

This is the paradox of moral transcendence: to reach a state of complete peace, detachment, or equanimity — as advocated by some philosophies and spiritual traditions — may require a retreat from engagement with suffering itself. But morality, by definition, demands engagement. It asks us to notice pain, to act in the face of harm, and to care.

In this light, “perfection” becomes not the moral ideal, but a moral hazard.

If a being reaches a point of such inward serenity that it no longer feels moved by the cries of others — if it can watch the world burn and simply remain at peace — then what value does that perfection hold?

This critique touches not just religious or mystical traditions (Buddhism, Stoicism), but also philosophical arguments like those of Schopenhauer, who emphasized withdrawal from desire and disengagement from the world’s suffering. While such renunciation may offer personal peace, it illustrates the moral hazard of indifference: detachment from suffering is not virtue, but abdication of responsibility.

True morality cannot end in apathy. It must persist in the presence of discomfort. It must be willing to stay in the room with suffering.

If moral perfection were even possible, it might actually be immoral — because it would imply the cessation of moral striving.

We propose instead a different framework: Moral Asymptoticism.

Like Zeno’s paradox33, our moral task is not to arrive, but to move ever closer. Not to achieve a final state, but to continually reduce suffering, refine our ethics, and expand our circle of concern. We are not meant to be perfect beings, but asymptotically moral ones — forever in motion, forever improving.

This view aligns with the constructivist ethic already outlined: morality is iterative, dynamic, and eternally incomplete. We do not wait for a cosmic referee to judge our progress. We refine our moral compass, recalibrate our frameworks, and move forward — even if perfection remains out of reach.

If transcendence is ever to be morally defensible, it must meet a single impossible condition:

All suffering must first be eliminated.

Only when there is no longer any need for moral action — when no sentient being suffers, when no harm remains unaddressed — can moral beings retire. Until then, detachment is desertion.

In this light, spiritual or technological transcendence is not a moral achievement, but a form of abandonment if pursued prematurely. The monk in the cave and the billionaire in the upload pod are not morally complete — they are morally absent.

This paradox also reshapes our understanding of creation itself.

A perfect being, lacking nothing, would have no reason to create. If creation exists — and we know it does — then we are faced with only a few possibilities:

The creator was imperfect.

The creator voluntarily became imperfect in order to create.

Creation is the product of beings who are not gods, but more like us — flawed, partial, collaborative.

Each of these options erodes the foundation of classical theism. A god that creates out of boredom or loneliness is no longer perfect. A god that creates and then abandons its creation is not moral. A god that creates and then intervenes — issuing commands, demanding loyalty, permitting atrocities — is dangerous.

The only moral position for a creator would be non-intervention — a position indistinguishable from deism or even atheism in practical terms.

And so, once again, we find ourselves alone — but not without responsibility.

To pursue morality is to reject the fantasy of arrival. It is to embrace incompletion. The moral task is not to escape suffering by rising above it — but to meet it, reduce it, and remain near it until it is gone.

Moral asymptoticism gives us a compass, not a destination. It tells us that perfection is not moral, and morality is not perfect. But movement matters. Striving matters. Attention matters.

In the end, we are not here to become gods. Even in a utopian scenario where all suffering has been eliminated, new forms of life which suffer might arise. Thus, our job will never be done, regardless of how long humanity ultimately survives.

One of the most paralyzing aspects of moral decision-making is the uncertainty it entails. We rarely act with perfect knowledge of outcomes, consequences, or even moral clarity. And yet, the world does not pause to wait for certainty. Decisions must be made. Suffering occurs regardless.

This introduces a paradox:

We cannot act with perfect moral knowledge — but we must act nonetheless.

To resolve this, we introduce what may be one of the most practical imperatives of the entire doctrine: the Moral Quantification Imperative.

At the heart of moral behavior is the goal to reduce suffering — but what exactly is suffering? Can it be measured? Compared? Ranked?

While these questions may seem impossibly abstract, we already live with imperfect answers:

Medical pain scales, such as the 1–10 pain index, help doctors assess subjective pain across patients.